RAGTIME

CONTEXT

RAGTIME takes place in and around New York City in the early 1900s.

Learn more about the real life places and events that inspired RAGTIME below.

In RAGTIME, Tateh and his daughter immigrate to the United States from Latvia. They are processed at Ellis Island, which was a real immigration station in the Hudson River near the Staue of Liberty.

Opened in 1892, the peak number of immigrants passed through Ellis Island from 1900 – 1914: about 1,900 people a day. The majority were from Eastern and Southern Europe, looking for a better life in America, and sometimes fleeing war or famine. This included many Jewish immigrants, like Tateh, who were escaping religious persecution. They traveled on steamboats on voyages that took 1-2 weeks, often in cramped, unsanitary quarters. Once they arrived, they went through medical and legal screenings. If they passed the screenings – and about 98% did – they could stay in the United States. About one third of the immigrants stayed in New York City, while others traveled on to other destinations.

In 1921 and 1924, laws were passed that significantly restricted the number of immigrants allowed into the country. The laws reflected the fears and prejudices many Americans had toward immigrants. While Ellis Island remained open as an immigration station until 1954, the number of immigrants coming through greatly decreased. But all told, Ellis Island processed 12 million immigrants. It’s estimated that 40% of Americans can claim at least one relative who came through Ellis Island. Ellis Island opened as a museum in 1990 and you can still visit it today.

ELLIS ISLAND

Immigrant Landing Station, 1905

New arrivals in the baggage room at

Ellis Island, 1905

HARLEM

The fictional character of Coalhouse Walker Jr. lives and works in Harlem as a piano player at the Clef Club, which was a real Harlem club for Black musicians in the 1900s. The Clef Club Orchestra was an all-Black orchestra that even played at Carnegie Hall.

The events in RAGTIME span the years 1902 – 1916. At the turn of the century in New York City, over half of the Black population were migrants new to the city, coming from the Caribbean or the Southern United States. Those coming from the South were an early part of The Great Migration, which was one of the largest internal migrations in U.S. history. Many Black Americans began moving North hoping to escape the racial oppression, terror, and violence of the Jim Crow South and seeking safety and better economic opportunities in the North.

While the North offered more social and economic freedom, there was still discrimination: Black people were increasingly pushed into segregated neighborhoods with substandard housing. And, as Coalhouse experiences in RAGTIME, Black Americans were subjected to systemic oppression, racial harassment, and violence. However, Black community organizations, churches, sports teams, businesses, bars and hotels also flourished during this time and contributed to rich cultural and social networks. In the few years after RAGTIME is set, the Harlem Renaissance was in full swing – the cultural and intellectual movement of the 1920s and 1930s that produced a wide range of significant Black artists and artwork.

Two influential Black leaders and activists at this time were Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. DuBois. Washington is also a character in RAGTIME. He believed in a gradual approach for achieving equality and emphasized vocational education and self-reliance. As the Washington character says in RAGTIME, he “counseled friendship between the races.” W.E.B. DuBois however, wanted immediate action and political change: he disagreed with Washington’s accommodationist approach. He was the first Black American to receive a doctorate from Harvard and advocated for higher education for other Black Americans. He was also a founding member of the NAACP. His ideas influenced the Civil Rights movement.

The fictional character of Mother lives in New Rochelle with her family. New Rochelle was – and still is - a wealthy suburb of New York City.

RAGTIME is set during the Progressive Era (1890s – 1920s) when upper-class women, like Mother, were not encouraged to work outside of the home.

The type of work open to women varied greatly by socioeconomic status and race. For many working-class women, work was physically demanding and dangerous. In 1900, about 20% of women were in the paid labor force and of those women, about 75% worked in domestic service, farming, or factories. Many factories hired immigrant women and children and paid them less than men. Women working in factories were exposed to dangerous working conditions, little pay, and long hours.

During this era, there was also a growing number of college-educated, middle-class women. Many worked in “caregiving” professions like nursing and teaching. Middle class women established settlement houses that provided social services, which was the start of social work as a job. There were also a growing number of women’s

clubs. Through these settlement houses and clubs, women had spaces to gather outside of the home, get involved in political and civic discourse, and agitate for change. They fought for social reforms in public health, education, worker’s rights, and voting rights.

Women had been organizing for the right to vote for decades prior to the Progressive Era. Finally, after protests, marches, petitions, and hunger strikes, women gained the right to vote in New York State in 1917 and nation-wide in 1920 with the passage of the 19th Amendment.

.jpg)

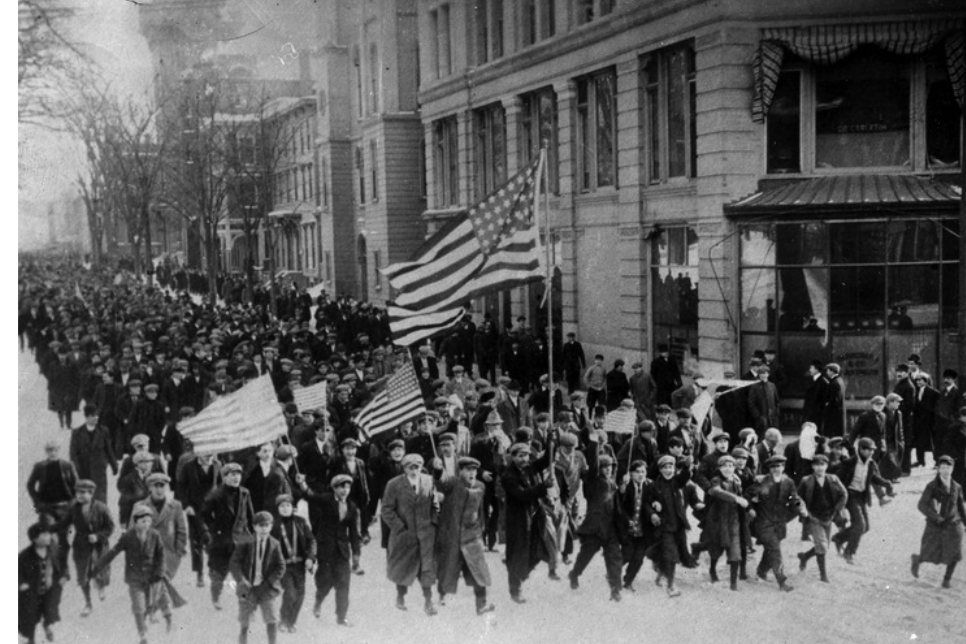

Suffragist Parade in New York City, 1917

NEW ROCHELLE

LAWRENCE,

MASSACHUSETTS

In RAGTIME, Tateh and his daughter are caught up in the Lawrence Mill Strike - a real and influential labor protest that took place in 1912.

Lawrence, Massachusetts was a mill town: about half of the population over 14 years old worked in textile mills - industrial facilities where cotton and wool were turned into fabric. Lawrence was also home to a diverse range of immigrants: there were people representing 51 different nationalities, and they all banded together to fight for their rights.

Mills were dangerous places to work. Workers often suffered from respiratory diseases and risked severe injury or even death from accidents with the heavy machinery. In Lawrence, a third of mill workers died within 10 years of starting their job. Workers were also not paid well and were expected to work long hours in physically strenuous conditions. Many workers were women and children, needing to earn money for their families. Child labor laws weren’t as strict at this time and the few laws in place often weren’t enforced.

In January 1912, after the mill owners cut their workers’ pay, workers decided to go on strike. Women weavers at the Everett Cotton Mills were the first to see that their paychecks were lower than usual. They walked off the job with shouts of “too short!” and were quickly joined by thousands of strikers from other mills. Strikers carried signs that read “We want bread, and roses, too.” Because of this, the strike became known as the Bread and Roses Strike. That phrase was used by James Oppenheim in his 1911 poem that was set to music and became a popular protest song. Listen to one version here: "Bread and Roses"

BOSTON

NEW YORK

Textile Mill in Lawrence

Lawrence Strikers

Protestors and police clashed, and several protestors lost their lives. Striking families decided to send their children out of Lawrence to protect them. When the children arrived in New York City, they were met by a cheering crowd of thousands. This event got media attention and earned sympathy for the strikers. When the strikers decided to send another group of their children to Philadelphia, police tried to stop them. Violence erupted as police officers in Lawrence beat women and children to prevent them from leaving. This event is dramatized in RAGTIME when we see Tateh try to send his daughter to Philadelphia.

News of the police brutality made it into the papers and caught the attention of President Taft and his wife. The President began an investigation into the conditions at the mills. During the hearings, mill workers, including children, testified about their experiences.

Public opinion had turned in favor of the strikers and the mill owners finally agreed to the organizers’ demands: 15% increase in pay, overtime, and no retribution for workers who had gone on strike. After nine weeks, the strike ended in March 1912.

.jpg)

Political cartoon from 1912 depicting the police preventing children from being sent to safety